The responsibility of the building to the street

Buildings are responsible for not imposing blank walls on the street. (Emma Avery)

A version of this article was previously published on Planetizen.

In 1962, the city of Halifax, Canada, demolished seven hectares of homes and businesses in the centre of its downtown to make way for a modern office-mall megacomplex called Scotia Square. It was designed according to the architectural trends of that time, with simple geometric shapes and blank external walls. The building was meant to revitalize the downtown, replacing worn-down buildings with something exciting and new. Instead, it cut downtown in two, demonstrating the consequences of letting buildings fail their streets.

Scotia Square was meant to revitalize Halifax, but instead divided it in two. (Halifax Municipal Archives, 1970)

The old Halifax buildings were poorly maintained, but they offered visual variety, and many had shops on their first floors. Old photos show vibrant, well-used streets.

Hennessy Street in the 1960s. Unidentified building. (Halifax Municipal Archives)

These buildings were replaced by long, austere, concrete walls, creating streets that few people were willing to walk on.

Scotia Square, Halifax. (Tristan Cleveland).

The construction of Scotia Square severed the city’s north end from the rest of the downtown. The neighbourhood, once bustling and prosperous, quickly asphyxiated.

I once asked a long-time resident of the area how long it took before businesses boarded up their windows.

“About two weeks,” she told me, her deadpan tone expressing resentment a half-century later for this still-unpunished crime.

The area’s main street, Gottingen, is only now starting to make a fitful, incomplete recovery.

Scotia Square created a barrier to the north end, but it was not a physical wall. Instead, it was an aesthetic barrier: Streets too bleak to walk on. The visual design of buildings matters because it shapes where people will and will not go. By routing people away from Gottingen Street, Scotia Square changed the economic trajectory of an entire neighbourhood, impacting the lives and economic future of the thousands of people who lived and worked there.

I propose that all building designers have a simple, bedrock responsibility which I call the “responsibility of building to the street.” In simple terms, it is the responsibility to create streets where people want to be. This is no less important than a strong physical foundation because it is itself the foundation of city life.

Visual design matters

Alain Bertaud criticizes urban planners for trying to make cities look like “Disneyland or Club Med.” Cities, he argues, are job markets, not vacation resorts. But is visual design frivolous? What if a practical “function” of buildings is to create human-friendly streets?

Nearly everything cities care about depend to some extent on creating streets where people can walk and spend time. To reduce traffic, air pollution, and carbon emissions, cities need people to drive less and walk more. But few people walk if streets are repellent.

When streets fail to support walking, it also contributes to higher rates of diabetes and other health problems. If residents rarely walk their streets, they are less likely to see friends or meet new people, which leads to higher rates of social isolation. Streets full of people create a sense of vibrancy, which then helps attract more people. Streets need people walking to make them safe from crime—to create “eyes on the street,” as Jane Jacobs famously put it. And streets need people walking to support busker festivals, food trucks, art showings, and other community events that depend on passersby.

When few people walk streets, it is harder to keep local businesses open. This affects everyone, but hits low-income people the hardest. Poor people are less likely to find work or escape poverty if there are few jobs or places to open a business near their home. They are also less likely to have access to healthy food if a neighbourhood lacks markets and food businesses.

Attractive design is not a luxury for the wealthy. One study found that people feel a stronger sense of attachment to their community if they rate it as attractive, and this is true for both the wealthy and the poor. If anything, low-income residents depend more on their streets being human-friendly. If buildings transform streets into gutters where people are scattered like detritus in the rain, the wealthy can pay to live and travel elsewhere. The poor must make do with the streets they have.

Fundamentally, cities are a collection of three things: Buildings, streets, and people. If buildings fail to create streets where people want to be, it makes it harder and less enjoyable to participate in city life, corroding everything that depends on human interaction.

Taste versus competence

One reason critics dismiss aesthetics is that they say it is a matter of taste. There is no objective yardstick to measure a building’s attractiveness or convince someone that one design is better than another.

While all this may be true, it misses the point. Consider the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain. Some people love it. Some do not. If I show you a photo and ask your opinion, your answer is a matter of taste.

Guggenheim in Bilbao, Spain, by Frank Gehry. (Wikimedia Commons).

However, one thing is measurably true: The building does not attract street life. Its blank walls and bare plazas create dead zones almost devoid of people in an otherwise bustling city. Whether the building is an artistic masterpiece or passé, it objectively fails in its responsibility to create streets where people want to be.

Entry plaza to the Guggenheim, Spain, is devoid of people. (Ethan Kent)

The responsibility of the building to the street is not to create buildings that look good in photographs. It is to create environments where real people are actually willing to spend time. It is the difference between designing model airplanes for an impressive photo shoot and designing airplanes to fly. The first is a matter of taste. The second is a matter of competence.

People-friendly design

Researchers have long analyzed the buildings and streets that attract the most people, and compiledlists of bestpractices that generally have much in common. Some key points:

Enclosure. Buildings should line up along the street to create a coherent edge, so that the street feels like a room with two walls and a floor.

Transparency. Buildings should have windows and doors at street level. Buildings should also bring human activity to the street to the extent possible—depending on the type of building and the nature of its occupants—using such features as porches, gardens, balconies, benches, retail entrances, or restaurant terraces.

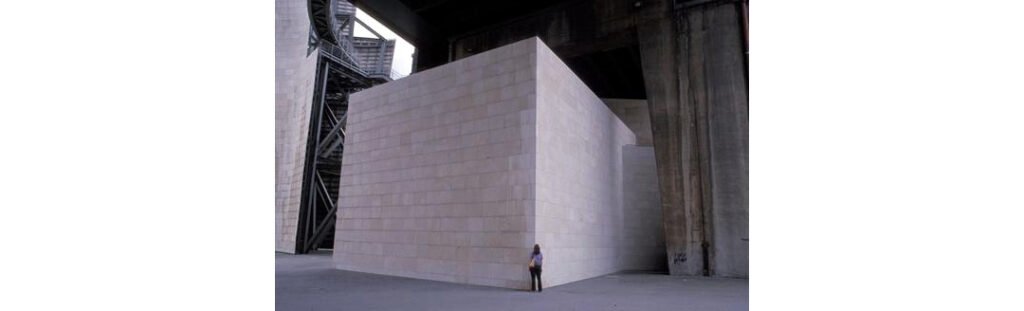

Human scale. Buildings should not impose large, uninterrupted walls that make people feel like ants.

Biophilia. Buildings should be lined with plenty of greenery.

Physical comfort. Buildings should offer protection from the elements. In hot climates, they should cast shadows and encourage a breeze, whereas in cold climates, they should maximize sunshine and minimize wind.

Visual diversity. Buildings need to provide the eye with lots of visual information at large and small scales.

Fillmore Street, San Francisco. (Creative Commons License)

The proof of these principles’ effectiveness is in the pavement. When one looks at a street that lacks these elements, the difference is obvious and profound.

Herring Cove Road, Spryfield, Halifax, Canada. (Tristan Cleveland).

Feeding the human eye

The human mind evolved to process complex natural environments. A view of nature improves our mood, our ability to focus, and even our health. Research suggests that the streets that attract people offer a similar level of visual information as natural spaces.

When buildings instead impose flat, empty walls on the street, pedestrians experience stress and discomfort. They walk faster, as if trying to escape. Eye-tracking software finds that our eyes skid across empty walls, like slipping on ice. Blank, flat buildings predictably repel people.

Building in a residential neighborhood, Halifax, Nova Scotia. (Tristan Cleveland)

Neuroscientist Colin Ellard has quantified the amount of visual information contained in a building facade. He finds that people are attracted to buildings with a minimum quantity of visual complexity at all scales, from large to small. Just as forests have trunks, branches, and leaves, buildings need large shapes and fine-grained details.

Cultures around the world have intuitively understood this principle. At large and medium scales, they divide walls with arches, pillars, porches, porticos, pitched roofs, window sills, awnings, railings, cornices, dormers, feature lines, and other elements. At a smaller scale, they provide plenty of details: The curves carved into arches and buttresses, the swirls in metal railings, the notches in roof lines. All of this, critically, is three-dimensional—something that can cast a shadow—not merely designs painted on a wall.

From the 1950s to the 1970s, few architects added ornamentation to buildings of any kind. Then, postmodernists like Frank Gehry started to turn buildings themselves into a kind of ornament, using elements such as the swooping roofline of the Guggenheim in Spain. However, providing small-scale decoration, such as the sculptures and notches that adorn window sills in many cultures around the world, remains taboo. Contemporary buildings often provide plenty to look at from a distance, but not when viewed up close from a sidewalk, where it matters most.

The resulting visual scenes are often so bereft of visual content, Nikos Salingaros observes they mimic the experience of having retinal damage.

The Guggenheim has ornamentation when seen from a distance, but lacks small-scale ornamentation when seen close-up. (Ethan Kent)

Ornamentation is taboo, in part, because architects perceive it as frivolous and unnecessary. But ornamentation serves a practical purpose. Visual detail is essential for creating an environment where people are willing to walk and spend time, which is essential to the economic, social, and environmental health of the city.

It is remarkable how taboo ornamentation has become. A developer I know had to fire an architect because he refused to add cornices to the roof of a building or details to its windowsills. The architect would rather lose a client than design human-friendly buildings.

A vocational duty

I recently visited an architecture school to give feedback on student projects. Their task was to design a building on the main street of Halifax’s north end, Gottingen Street. Given the tumultuous history of the street, I expected students to explain how their buildings would contribute to helping it recover. But of the nine projects I reviewed, only one mentioned the impact of their proposed building on the street.

These students have a practical, essential role to play in society, if they choose to accept it: to create buildings that improve human life. It is a worthwhile responsibility, a vocational task, and a skill to hone, like being a doctor. Instead, they chose to focus on abstract concepts.

Buildings must stop turning streets into empty places that people are forced to trudge through. Buildings can, and must, create joyful streets that residents love, where they can lead worthwhile lives. To consistently create great places, designers must recognize their fundamental responsibility to the street and implement it with pride and purpose.