Architecture helped me heal. So I helped create a new guide to fight loneliness

Five years ago I went through a personal health crisis. In a matter of weeks I completely lost my independence; I went from running half-marathons to not being able to walk 100m without feeling like I was going to faint. Someone needed to be with me at all times in case of a seizure. Anxiety and depression set in.

I couldn’t keep up with my work, so I pressed the pause button on my PhD and delegated existing architecture contracts to colleagues. I pushed many of my friends away because I didn’t know how to explain what was happening to me — and I dreaded the sympathy faces.

A mix of medicine, therapy and a supportive network of close friends and family got me through this sour stage of my life. But one of the crucial changes that kickstarted my recovery was moving from my apartment in Mexico City’s Acacias area to a new home in Tlaco.

Why am I telling you this? Because what I learned during my health crisis led me to my life’s mission and passion — to design buildings that make people happier and healthier. The positive effects that my new home had on me opened my eyes to the transformative power of architecture. Architects often go to great lengths to craft the perfect form and aesthetic that suits their style, but not enough architects take steps to ensure that their buildings are designed to foster wellbeing.

The 2007 Crystal addition to the Royal Ontario Museum, while being visually striking, created a harsh environment that seemed to repel pedestrians. Credit: the City of Toronto (CC BY 2.0).

Architecture for health and happiness

So how did my new home help me recover? The answer comes from how my new building was designed, and in the nature of the buildings, streets and public spaces that surrounded me in my new neighbourhood. Let me explain:

Natural Light: Unlike my earlier living situation, my new apartment had an open floor plan that maximized natural light — known to reduce fatigue, sadness and feelings of depression.

Outdoor Space: My new home also had access to outdoor space via our third-floor balcony. I would take my morning tea there, and even when I didn’t feel like going out, I got some fresh air and got to be part of public life. Access to outdoor spaces, even if only private balconies, can strengthen our sense of connectedness.

Co-Living: I got a boost in sociability through co-living. Our new apartment was a three-bedroom, and since my partner and I couldn’t afford the rent, we invited a friend to come live with us; the spare room was our home office. This meant having friendly dinners, always having someone to talk to, meeting new people and sharing stories.

Pets: My previous building had a strict no-pet policy, but my new home was in a pet-friendly apartment. Many people know that pets can relieve depression, but what most people don’t realize is that pets provide a way to connect with passersby and other pet owners. I made new friends through my dogs and these connections helped my recovery.

Interesting Streets: My old neighbourhood was grey and drab. Blank facades dominated the surrounding buildings, making the streets feel like uninteresting — and unsafe — places to walk. In my new neighbourhood, buildings have storefronts, coffee shops, doors and windows; research shows that a variety of visual cues like these brings us more joy and less stress while walking.

Walkability & Transit: In my new neighbourhood, a mix of shops, services, public spaces and lots of nature within walking distance give me a reason to go out on foot — which was healthy and restorative for me in multiple ways. I also had easy access to transit and cycling infrastructure. When I was strong enough to commute, switching the stressful traffic jams of Mexico City for a bicycle or a transit trip on dedicated lanes reduced my daily stress and increased the time I could spend with loved ones.

As designers, there are so many decisions we can make to improve the way people live. This experience opened my eyes to the power, and responsibility, of those who design the places we live. We can build better cities. We can and must build better buildings — ones that make us healthier, happier and more socially connected.

Above: The old neighbourhood was grey, unwalkable and unfriendly. Below: The new neighbourhood was rich with parks, great sidewalks and small, streetside businesses

The Happy Homes project

This is what we do now at Happy Cities. Our ongoing Happy Homes project is a design and policy tool that is helping cities and developers all around the world promote wellbeing and social connectedness through multi-unit housing.

The project brought together more than 40 experts in architecture, urban planning and public health to understand and develop solutions that will transform multi-unit buildings into catalysts of strong and connected communities.

And here is a bonus to you for reading this far: you can have this tool for free!

The toolkit is divided into 10 principles that have been translated into design, programming and policy strategies. In each strategy there is a list of actions to improve sociability and wellbeing. Some of them are low-hanging fruit, while others are bold moves that require cooperation from different levels of government.

One of the easier steps has already been tested by the City of Vancouver through the Hey Neighbour pilot project. By hiring one of the residents to be a social concierge, we helped residents build supportive networks to organize daycare, dog walking groups, gardening activities and workshops, among other things. This can be implemented in any new or existing building!

Evidence shows that our sense of belonging is strengthened when we work, play or create together. These kind of activities build feelings of mutual trust, which in turn boost our sense of safety and our ability to tackle big challenges together.

Solutions — and solutions to the barriers to the solutions!

One of the biggest insights we learned is that we need to ensure that multi-unit buildings — especially mid- and high-rise buildings — offer opportunities for social encounters. Such interactions counteract feelings of being overcrowded and isolated.

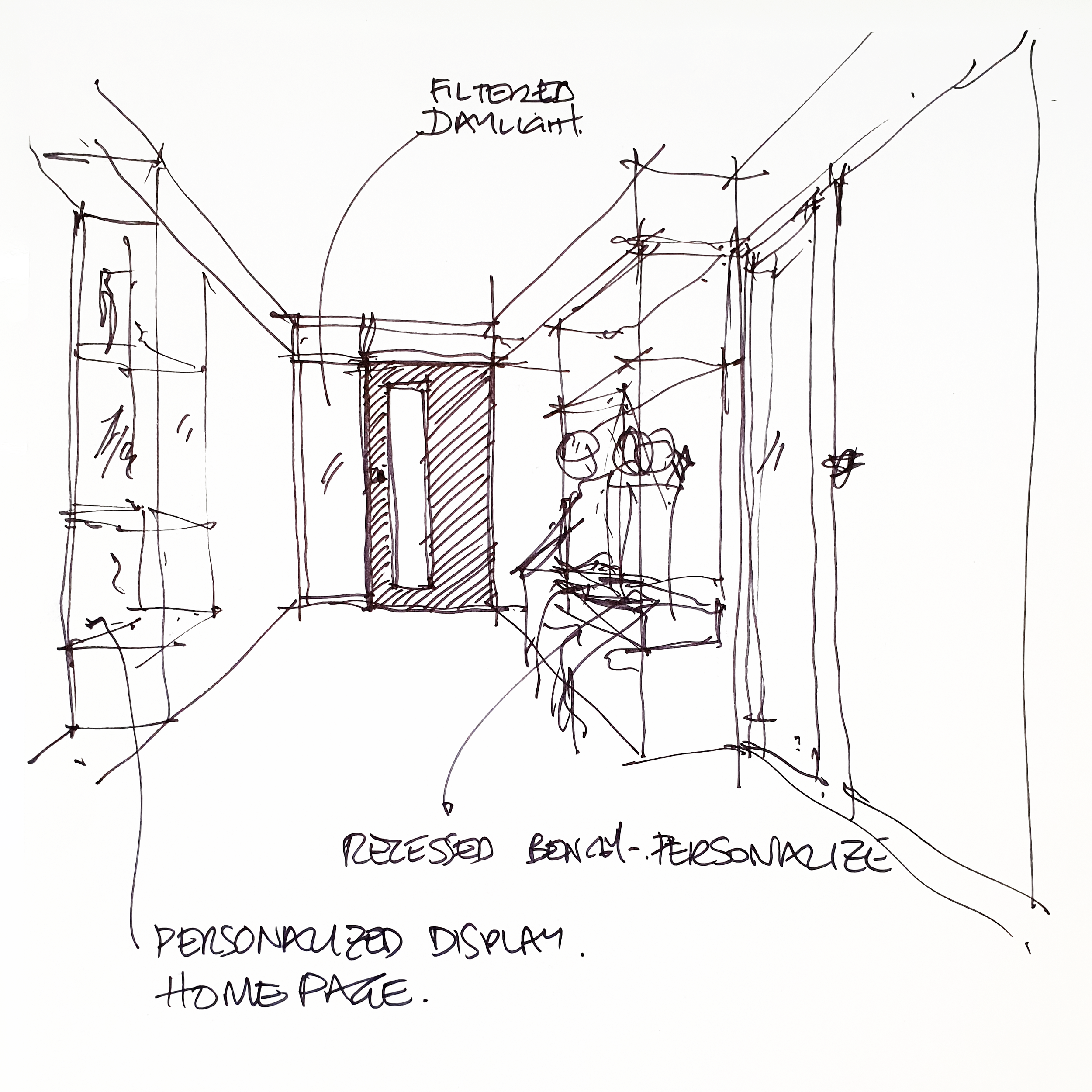

One approach is to widen shared corridors and incorporate features into them that encourage casual engagement between neighbours. Examples are book nooks, reading chairs or an area for shared tools. We can even expand the common areas near stairs and elevators to create spaces for potential interactions, via the introduction of a sofa, bookcases, or galleries.

Design like this comes at a cost for developers, so we need to tackle a few barriers to make this possible. The good news is that the agendas of planners and developers are not that different! When we interviewed members of the housing industry, we found out that their priorities were very much aligned. It is just about finding the right mechanisms — such as FSR exclusion, bonus density, setback relaxations, or fast-tracking of applications, etc. We have collected and explored these practical tools that mitigate the financial, social or policy barriers to happier, healthier design.

There are so many ways to promote wellbeing and social connectedness when we are designing multi-unit housing. Imagine having a community garden on your rooftop, or a flexible space that can be used as an office, daycare or workshop depending on residents’ needs. Or a wall made available for kids to paint. What if we installed planter pots that grow herbs and greens to teach children about the miracle of growing food? The Happy Homes report lists many of these ideas.

We can build amenities that are just for residents, but also build others for the whole community. What about a local shop in the ground floor of your building where one of the neighbours sells self-produced local crafts and coffee?

We can even build flexible units so that as the number of family members changes, the space where they live can adapt — expanding or shrinking as needed.

Interventions like these extend the tenure of residents, boost their wellbeing, and increase feelings of safety and engagement.

This is all possible!

The time to make these changes is now

As most of us know well, global urbanization is gaining speed. By 2050, nearly two-thirds of all people will be living in cities. This puts a lot of pressure on housing. We need to ensure that while we densify our cities, we continue to provide livable and healthy environments where people are happy and can thrive — places of social resilience.

We spend more than 16 hours in our homes every day. We need to build housing where we feel happy, where we trust our neighbours, where we can age, and where we can heal in case we — or our loved ones — get sick.

We need to build homes that push us forward, carry us when we’re down and nudge us to come together with others in good times and bad times. These are the cities of a better future.

The Happy Homes project was funded and supported by BC Housing and the Real Estate Foundation.